Countryside southeast of Tam Diep, Vietnam.

Submitted photo

Man with the author in Vinh, Vietnam.

Submitted photo

Traffic in Phnom Penh, Cambodia.

Submitted photo

Woman hauling produce on her bike in Ninh Binh, Vietnam.

Submitted photo

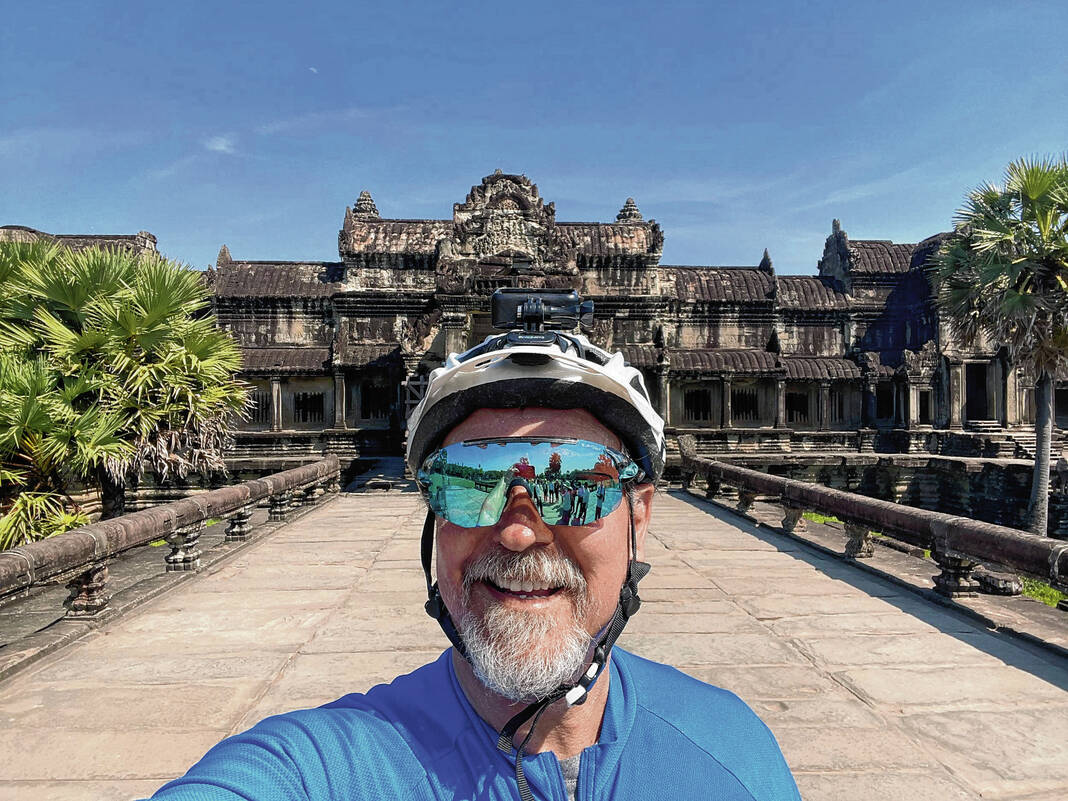

Ancient City of Angkor Wat, Cambodia.

Submitted photo

Scarecrows alongside workers in rice paddy fields in rural Vietnam.

Submitted photo

Huge statue of Buddha in a park south of Da Nang, Vietnam.

Submitted photo

Iguana sitting on a bicycle seat in Vinh, Vietnam.

Submitted photo

Ferry ride across Ham Luong River in Mekong Delta, Vietnam.

Submitted photo

A tractor used in rice paddy fields in rural Vietnam.

Submitted photo

Vietnamese women planting rice stalks in rural Vietnam.

Submitted photo

Motorbike bridge in rural Vietnam.

Submitted photo

Woman working in her garden in a Cambodian village.

Submitted photo

Craig Davis

l haven’t lived in Jackson County for decades, but I am intrinsically linked to it in many conscious and subconscious ways.

I dream about Brownstown and Freetown frequently. I conduct research on Kurtz. I visit family, read The Tribune and then occasionally, I stumble into a situation that triggers memories.

On Mother’s Day this year, I walked to the La Colonia supermarket in Tegucigalpa, the capital of Honduras. On a Sunday morning, the streets are relatively safe. I needed to buy some groceries so I could make tuna melts for my daughter and grandchildren, and I always need the exercise.

I had spent the early morning researching and writing about Kurtz in 1908 before my walk. After I returned home, I would revisit three teenage experiences in a matter of moments. Like everyone else, I am a product of sophisticated composite of experiences, relationships, DNA and other factors complexly woven into the texture of my personality.

Take the simple act of changing a flat tire. When I was about 13 or 14, I was riding in the back seat of my mother’s Torino one night, returning a movie in Seymour. I think the film was “The Poseidon Adventure.” Suddenly, the car suffered a flat tire on U.S. 50 about halfway to Brownstown. We piled out, opened the trunk and found the spare tire and the jack.

As the oldest male, I was expected to somehow miraculously know how to change it. But no one had ever shown me. The other passengers made fun of me, and I grew very embarrassed.

A couple of years later when the car I was riding in experienced a flat on the same road on the way to Seymour, I found myself as the only male in the car. And again, the responsibility fell to me. But this time, I felt more confident. I had seen my uncle change a tire, so I quite proudly jacked up the car, removed the flat and attached the spare.

A half an hour later at the tire shop, the repairman walked out and looked at my handiwork and asked, “Who put this tire on?”

When I admitted it was me, he said, “This is dangerous. See how the lug nuts are on backwards. If you had driven much further, it would have sheared the studs off” and caused an accident. I was humiliated.

Eventually, I learned to change a tire and have changed my fair share over the years.

On this Mother’s Day morning, as I was returning from the La Colonia supermarket with a few groceries, I came across a car parked on the side of the street. A Honduran teenage boy, his younger sister and his mother were debating how to change a flat tire.

The act of being a Good Samaritan in developing nations can prove dangerous. In Kenya, the United Nations security officials taught us to never stop and help a stranded driver because criminals frequently pose as stranded drivers in order to rob the would-be rescuers or even carjack them.

Honduras is no safer. A few years ago, a work colleague of mine rolled down her window at a stoplight to give a beggar a few Lempiras only to have a second man sneak up from behind, put a pistol to her head and liberated her of her phone.

But within a few seconds of processing the Honduran teen and his family on this Mother’s Day, glimpses of my first two humiliating experiences with changing tires flashed through my head, and a third Jackson County lesson simultaneously struck a cord.

One hot summer day around 1976, Barry, a friend of mine, and I were traveling in his Jeep when we encountered a stalled car in the middle of our lane. Much to my surprise, Barry stopped. We helped the driver push the car off the road and onto the shoulder. Then we resumed our journey. Barry explained we should always help others in need. It’s just what country folk did.

So I set my groceries on the sidewalk and offered to help the Honduran family. The situation looked innocent enough, and the teenage boy was clearly struggling under the scrutiny of his mother.

Most Hondurans are kind. So many have treated my family and me hospitably. And I didn’t want the teen to suffer the same humiliation I had. As we removed the flat and attached the spare, I offered the youth words of encouragement.

“You were doing just fine without me … You would have changed it with no problem,” I said. “But I am happy to help.”

Just as we were putting the flat in the trunk, the father arrived in another car. We exchanged an abundance of handshakes and congratulations on a job well done. I pulled a pineapple pastry out of the La Colonia bag and gave it to the little girl.

As I walked the last half-mile home, I thought about these three Jackson County memories. About my failures and humiliations. About how I always seem to learn lessons the hard way. So many things I cannot fix. But somehow, I felt just a little bit better about the universe. When I arrived home, I made tuna melts for Mother’s Day lunch.

Craig Davis, who was born in Seymour and graduated from Brownstown Central High School, currently lives in Tegucigalpa, Honduras, and works for a U.S. government contractor on school-based violence prevention. He is the author of “The Middle East for Dummies” and is conducting research for a genealogy and social history book in Kurtz and Freetown. You can visit the Living with Cancer weekly blog at marvingray.org and write him at [email protected]. You also can follow his travel blog, “Cross-Country Bike-Packing at 63: SE East Asia,” at marvingray.org. Send comments to [email protected].